One of the coolest things we’ve borrowed/nicked from friends over here is a book called England’s Thousand Best Churches. A few of my colleagues and parishioners have jokingly taken umbrage at the name, so it really should have the subtitle “From a Historical and Architectural Perspective”. It divides these churches by county and has some interesting information about each church. I’m not going so far as to say that I’ve made it a goal to visit ALL 1,000 churches….but I do have to admit that I’m tempted. (Ian and Jenny, we WILL give the book back….eventually.)

We attempted to see a few of these churches our first autumn in Surrey, but, although lockdowns had technically lifted, the continuing Covid rates meant that many of these sanctuaries were closed and could only be seen from the outside or by standing directly inside the entrance. On that trip, we visited Dunsfold (and while we could only hover by the door, we did return for a Sunday morning service a few months later and were welcomed by their lovely congregation and priest), Hascombe (again only from the entrance), and Shere (where we were only able to see the outside).

A few weeks ago, we decided to continue this journey. We decided to only visit a couple this trip, to allow ourselves to a bit more time in each. We began at Albury, a small village about 15 minute drive to the east in the Surrey Hills. The church was “Old St. Peter’s and St. Paul’s” and is actually outside the village in Albury Park, a 150-acre park dominated by an old Manor House. When we arrived, we realised that the definition of “park” was the original one, meaning “hunting ground for the nobility”. While they probably weren’t nobles, there was a definite upper-class event going on. Dozens of Range Rovers, Land Rovers, and other various expensive SUVs were parked all near the entrance. As we drove through to the church, we saw groups of men dressed (more or less) exactly like you would picture English gentleman dressed for hunting, right down to the necktie, hound dogs trotting at their heels and pheasant carcasses hung down their backs. I looked around for cameras to see if this was filming for the new Downton Abbey film, but it seemed this was perfectly normal.

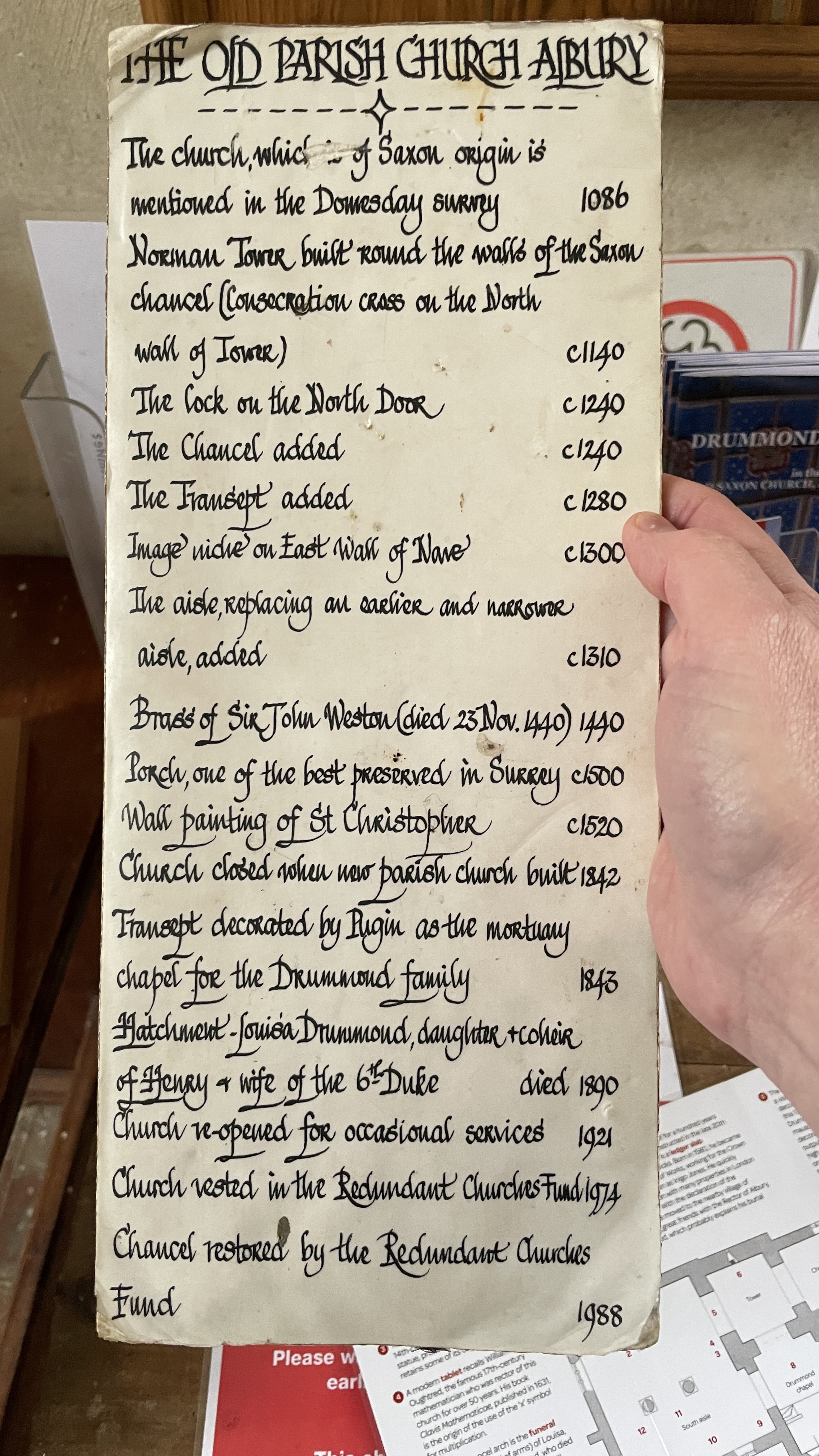

Anyway, after an appropriate time of gawking, we made our way to the church itself. Dating from the Saxon period, probably 12th century, it’s been added to repeatedly over the centuries.

The porch (which you can see over Lizzy’s shoulder above) was added in the 15th century. The door to the inside dates from the 13th.

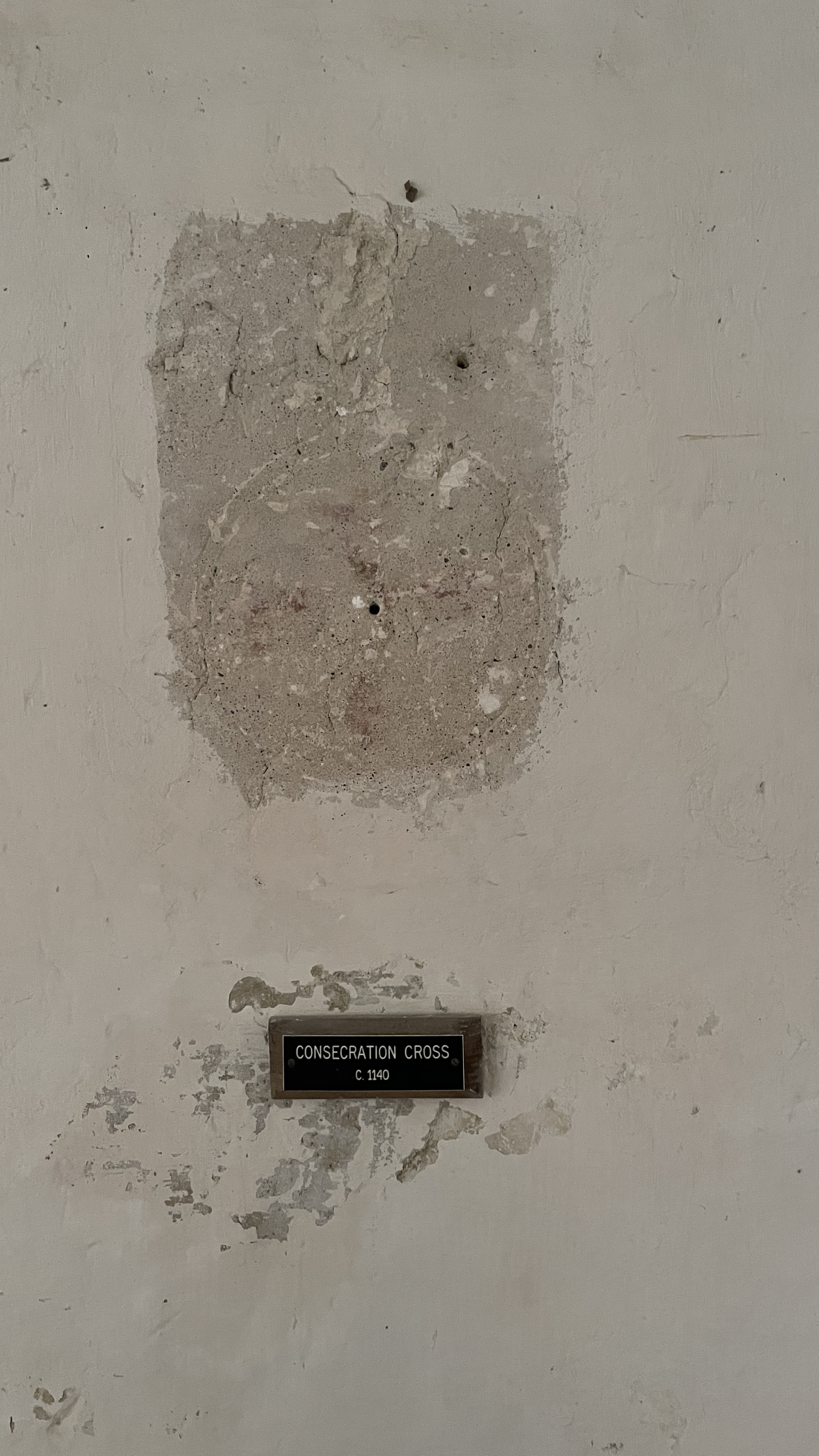

The church itself is no longer used for regular worship, so it’s very sparse inside. However, there are a few leftover relics that make it worth the trip. The baptismal font (below with the Poinsettias on it) is believed to be from a Roman Temple in nearby Farley Heath. Opposite are the remains of an 11th Century cross carved into the wall. Above the south door can still be seen a wall painting of St. Christopher (c1520).

Among the curiosities is a small side chapel, added in the 1800’s, for Henry Drummond, the then owner of the Manor. Drummond was involved in a small Protestant sect called the Catholic Apostolic Church, a Second Advent movement led by a Scotsman named Edward Irving. Drummond built a newer Gothic-style church nearby, where the CAC movement apparently worshipped until the 1950’s. That church sits empty, but extremely well-maintained, including electronic gates and locks, to this day.

After lunch, we moved back toward Godalming to a church that I didn’t realise was on the list: the parish church in the nearby village of Compton. It was harder to get a picture of the church exterior as the church is hemmed in rather closely by trees and houses on either side, but it is still a nice sight walking up the path from the road.

The church dates from the Norman Era, but relics found while doing work on the church foundation suggest that the site has been occupied since Roman times. A typically imposing door opens on to a beautifully maintained building which houses an active church community.

It’s most unusual feature, seen in the photos above, is a “double-decker sanctuary”, the only one to survive in England. No one is really sure what the upstairs gallery was used for. It’s place directly above the altar seems to preclude extra seating for the congregation as they would not be able to see the Mass. Some historians suggest it could have been a viewing gallery for a relic visited by pilgrims on the road to Canterbury, but even the accuracy of such pilgrims using this route is disputed.

However, the church was definitely used for a rather interesting bit of Church history, that of the anchorites. Anchorites were one of the earliest forms of English monasticism. These were people that decided to separate themselves from society in order to lead a life of prayer. Rather than monasteries or convents, though, they sought this separation right in the local parish church. They would be walled up in a small cell inside the church, spending their days in prayer and self-denial. Food would be passed in to them regularly (and presumably waste passed out, but no accounts seem to mention that). Such a cell exists in St. Nicholas. It was difficult to get a good picture of due to the space constraints, but there are two photos below I want to show. The first is a picture of where the anchorite would have spent their day kneeling, looking through a small window (the second picture) on to the altar and the cross.

Apparently there were a number of people in Compton who felt called to such a life over the centuries. During recent foundation work, six skeletons were discovered buried under the cell, suggesting that at least that number dedicated their life in such a way.

My favourite part of St. Nicholas was a different curiosity. Beside the pulpit are a couple examples of 12th century graffiti. They’re a bit difficult to make out, and, I’ll be honest, I have no idea what the first one below is. The second one, however, is fascinating. Supposedly carved by a knight before he left for the Crusades, he reportedly added the cross upon his return as a kind of thanksgiving.

Well, this post ended up being way longer than I intended, but we had some good stuff to show off. Next week, keep an eye out for a post about the church Panto, and the very unique English tradition of the Pantomime.